A large proportion of the New Testament contains letters from Paul, and there are also letters from James, Peter, John and Jude. It’s good to remember that God has divinely inspired the biblical authors to use forms of writing that were current and understandable in the time in which they were written, and which remain so today. This is part of God’s accommodating himself to us so that we can understand the gospel and what he requires of us. Let me comment on several features of the New Testament letters that will help you as you read them.

The letters are written for a specific audience

The letters are not works of systematic theology. Thank God for good systematic theology books, but that is not what the letters are. Rather, the New Testament letters, and especially those of Paul, are what scholars call ‘occasional’ documents, which means that they were written as specific responses to a pressing situation in a particular context.

Paul and the other authors did not write with a view to presenting theological or pastoral teaching in the abstract. Their aim was to deal with the pressing needs of the churches of their day. Under God, this explains the abiding relevance of the letters to us, and therefore the theology we learn from them is timeless truth.

The letters deal with specific issues

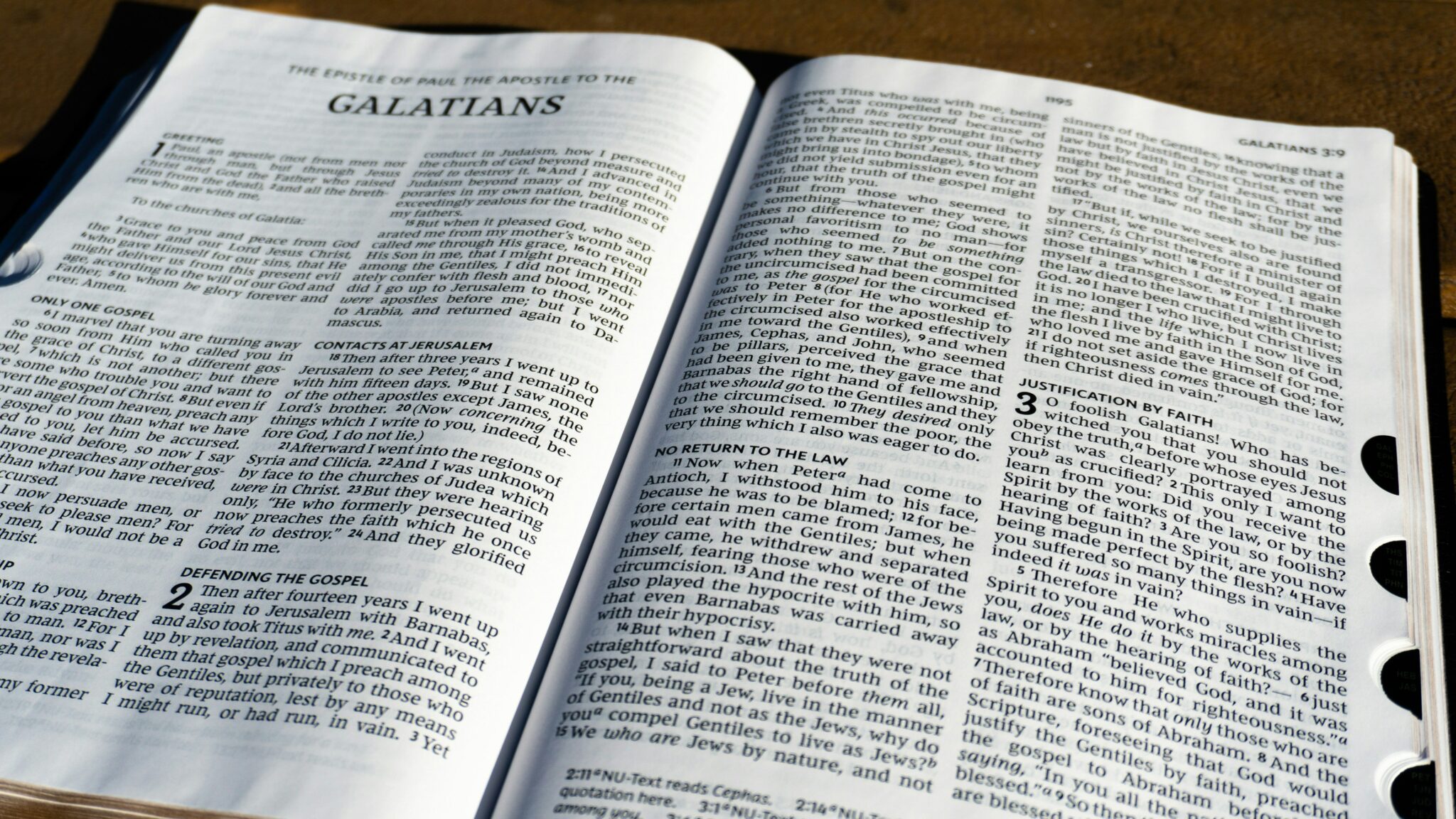

The specific audiences faced specific issues, so the letters seek to deal with these. They do so by bringing theology to bear on practical matters of Christian living. In Galatians, for example, the problem is a bad theology of the law. The opponents of Paul were teaching ‘a different gospel’ (Gal. 1:6), stating that works of the law were necessary to salvation which they expressed in following circumcision and ceremonial food laws. Paul is adamant in his response: ‘we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Christ’ (Gal. 2:16).

Yet there is also ethical teaching in Galatians as Paul seeks to remind his readers that grace does not encourage loose living. He reminds us of the awesome reality of union with Christ (Gal. 2:20) which means that Christ lives in us by his Spirit. Therefore we will have a desire to ‘walk by the Spirit’ and not ‘gratify the desires of the flesh’ (Gal. 5:16).

Paul deals with the issue of the law in Galatians in a way that is both theological and practical. He gives us a full-orbed presentation of the gospel that calls on us to produce the fruit of the Spirit based on the awesome reality of being justified by grace.

The letters teach us about Christ

However, we must be careful not to focus only on the doctrine and practical teachings of the letters and fail to see that they lead us to know and love Christ more. Paul knows that it is by ‘beholding the glory of the Lord’ that we ‘are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another’ (2 Cor. 3:18).

As an example, consider how Paul seeks to kill incipient disunity in the church at Philippi. In Philippians 2 verses 6-11 we have one of the greatest passages on Christ’s person and work in the whole New Testament. It traces the U-shaped curve of his humiliation and exaltation. He is in the form of God but takes the form of a servant. He becomes obedient to death, even death on a cross. Therefore, God has highly exalted him. It is an amazing passage, but note that its context is to teach the Philippians, who were tempted to quarrel, to humble themselves and to prefer each other’s needs before their own. ‘Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus’ (Phil. 2:5), is Paul’s point. They too were to follow the U-shaped curve of humiliation if they were to know exaltation. If relationships within the church seem impossible, Christ’s humility teaches us to go lower still to preserve peace. It is such people who are exalted.

The letters combine theology and life

The letters of the New Testament teach theology for life. This is true in the letters of Peter, James, John and Jude. Let’s take James 2 verses 1-13 as an example. The very practical warning there about the sin of partiality is rooted in gospel truths, which is often overlooked in considering James. Note the theology underlying the command not to show partiality. Verse 1 says, ‘Show no partiality as you hold the faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, the Lord of glory.’ Here again is high Christology. Verse 5 says, ‘Has not God chosen those who are poor in the world to be rich in faith and heirs of the kingdom, which he has promised to those who love him?’ Here is the doctrine of God’s electing love (see also 1 Cor. 1:26-31) and the promise of reigning with Christ in his kingdom. It is then that James calls us to ‘fulfil the royal law according to the Scripture, “You shall love your neighbour as yourself”’ (Jas. 2:8). James does not revert to law and works. Like Paul, he bases commands upon God’s gracious salvation.

In this focus on theology and life, there is a pattern observable in both Paul and James as well as others. The imperatives (that which we must do) are based upon the indicatives (that which God has done and what is therefore true of us). Getting this order right is essential and is the great genius of the New Testament letters in teaching us how to live the Christian life. Let us consider, to use Stuart Olyott’s phrase, how Romans unpacks ‘the gospel as it really is.’ After eleven stupendous chapters, Paul turns to the practical application:

I appeal to you, therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship (Rom. 12:1).

To understand how the letters relate doctrine and life, look out for the word ‘therefore’ and similar words. We must see that the demands to holy living are not the small print, or our side of the bargain that we must keep. We obey ‘by the mercies of God’. Our obedience is in fact a continued receiving of God’s grace. We need the letters to give us both a full-orbed view of Christ himself, what he has done for us in the gospel and how we can live for him.

So take up the letters and read!